El Significado Que Nos Dejo Monseñor Romero

Blog por José Fidel Campos Sorto

“Yo conoci por primera vez a Mons. Romero en 1975. Yo tenía 16 años, él llegó en visita pastoral a mi pueblo Sesori en donde mi papá era el sacristán. Me dio la impresión de un Obispo piadoso; luego constaté su actitud solidaria en visitas que mi padre le hizo a Santiago de María. En 1979, en San Salvador volví a constatar esa cualidad incrementada de su persona hacia los necesitados.

La conversión de Mons. Romero fue un proceso gradual que para él significó ser abierto a conocer la realidad, y su sensibilidad al sufrimiento de la gente. En 1977 fue nombrado Arzobispo y tomó posesión ante la algarabía de los ricos y la desilusión de los pobres. Pero los cuerpos de seguridad del gobierno generalizaron la represión al grado que solamente poco después le asesinaron a su mejor amigo, el padre Rutilio Grande. De ahí en adelante, se fue produciendo un giro en monseñor Romero; pues ya no se trataba solo del padre Rutilio; sino de catequistas, sacerdotes, obreros, campesinos que aparecían descuartizados por los cuerpos represivos.

La conversión de Mons. Romero fue un proceso gradual que para él significó ser abierto a conocer la realidad, y su sensibilidad al sufrimiento de la gente. En 1977 fue nombrado Arzobispo y tomó posesión ante la algarabía de los ricos y la desilusión de los pobres. Pero los cuerpos de seguridad del gobierno generalizaron la represión al grado que solamente poco después le asesinaron a su mejor amigo, el padre Rutilio Grande. De ahí en adelante, se fue produciendo un giro en monseñor Romero; pues ya no se trataba solo del padre Rutilio; sino de catequistas, sacerdotes, obreros, campesinos que aparecían descuartizados por los cuerpos represivos.

Los Escuadrones de la Muerte, amparados en el Ejército del gobierno, sacaban de sus casas a las víctimas en presencia de sus familiares u otros testigos que luego daban testimonio al Socorro Jurídico, institución creada por el Arzobispo para velar por los derechos humanos.

Para los diferentes sectores populares, víctimas de la despiadada represión, monseñor Romero llego a ser la única Voz de los que no la tenían. Cada misa dominical era escuchada con devoción, porque además de ser una catequesis de formación cristiana, él denunciaba los hechos represivos de ambos bandos, y especialmente de la Fuerza Armada. Para nuestro pueblo, monseñor fue un dignificador de la persona humana. Para las mayorías populares, monseñor fue el único referente calificado que daba esperanzas al pueblo desde la palabra de Dios.

Vimos monseñor com la persona que privilegió el diálogo como salida a la crisis del país. Para nuestro pueblo, Mons. Romero fue un modelo de hombre verdaderamente libre para decir la verdad oportunamente, sin odio y con respeto. Cuanto necesitamos eso en nuestros días!. Monseñor Romero trascendió nuestras leyes jurídicas cuando afirmó que éstas deben estar al servicio de las personas y no al revés. De ahí que, ante la brutal represión desatada por las Fuerzas Armadas en contra del pueblo, Monseñor Romero les dijo:

Vimos monseñor com la persona que privilegió el diálogo como salida a la crisis del país. Para nuestro pueblo, Mons. Romero fue un modelo de hombre verdaderamente libre para decir la verdad oportunamente, sin odio y con respeto. Cuanto necesitamos eso en nuestros días!. Monseñor Romero trascendió nuestras leyes jurídicas cuando afirmó que éstas deben estar al servicio de las personas y no al revés. De ahí que, ante la brutal represión desatada por las Fuerzas Armadas en contra del pueblo, Monseñor Romero les dijo:

“Yo quisiera hacer un llamamiento muy especial a los hombres del ejército…. Hermanos, son de nuestro mismo pueblo, matan a sus mismos hermanos campesinos. Ante una orden de matar que dé un hombre, debe prevalecer la ley de Dios que dice: no matar. Ningún soldado está obligado a obedecer una orden contra la Ley de Dios. Ya es tiempo de que recuperen su conciencia y obedezcan antes a su conciencia que a la orden del pecado. La Iglesia, defensora de la Ley de Dios y de la dignidad humana, no puede quedarse callada ante tanta abominación”.

Estas fueron las palabras de monseñor Romero que tocaron las fibras de la fuerza Armada y de sus Escuadrones de la Muerte, quienes le asesinaron al siguiente día lunes, 24 de marzo de 1980.

Estas fueron las palabras de monseñor Romero que tocaron las fibras de la fuerza Armada y de sus Escuadrones de la Muerte, quienes le asesinaron al siguiente día lunes, 24 de marzo de 1980.

Este hecho significó para nosotros como pueblo, una inmensa pérdida de nuestro defensor y guía espiritual. De ahí en adelante monseñor Romero ha sido considerado y venerado como un Santo. Luego de su asesinato, nos sobrevino un estado de indefensión generalizado que nos obligó a muchos a salir del país, otros nos incorporamos a la guerra, y otros a sobrevivir en medio de la misma guerra.

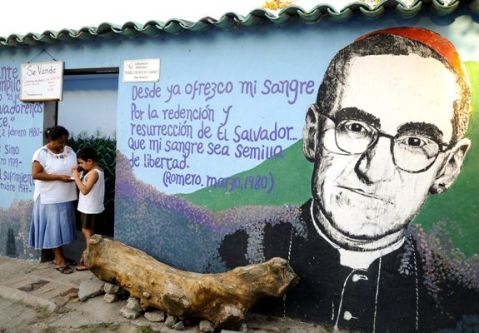

A 36 años de aquel magnicidio, constato que el mensaje del profeta Oscar Romero trascendió a su espacio y a su tiempo. Hoy es un salvadoreño universal, que con su mensaje siempre nuevo sigue iluminándonos los problemas sociales que nos aquejan en El Salvador – y yo digo que en todo el mundo. Por ejemplo cuando él mismo lo dijo: “Yo denuncio, sobre todo, la absolutización de la riqueza. Este es el gran mal de El Salvador: la riqueza, la propiedad privada como un absoluto intocable y ¡hay del que toque ese alambre de alta tensión, se quema!”(1979).

Las palabras de Romero tienen mucha relevancia hoy. Por ejemplo, sobre el tema de migración, tan presente hoy en nuestro tiempo, Romero dijo: “Es triste tener que dejar la patria porque en la patria no hay un orden justo donde puedan encontrar trabajo”(1978).

Las palabras de Romero tienen mucha relevancia hoy. Por ejemplo, sobre el tema de migración, tan presente hoy en nuestro tiempo, Romero dijo: “Es triste tener que dejar la patria porque en la patria no hay un orden justo donde puedan encontrar trabajo”(1978).

El mensaje de Monseñor Romero me interpela, tiene aplicación actual, por eso creo que el pueblo no lo ha olvidado, y sigue estudiando sus homilías para renovar fuerzas y seguir luchando por la justicia social de nuestros pueblos.

Para finalizar, me uno al llamado que monseñor hizo en su momento (1977): “No teman los conservadores, sobre todo aquellos que no quisieran que se hablara de la cuestión social, de los temas espinosos, que hoy necesita el mundo. No teman que los que hablamos de estas cosas nos hayamos hecho comunistas o subversivos. No somos más que cristianos, sacándole al Evangelio las consecuencias que hoy, en esta hora, necesita la humanidad, nuestro pueblo”.

Por José Fidel Campos Sorto

Este link es una canción de Mejía Godoy sobre Monseñor Romero:

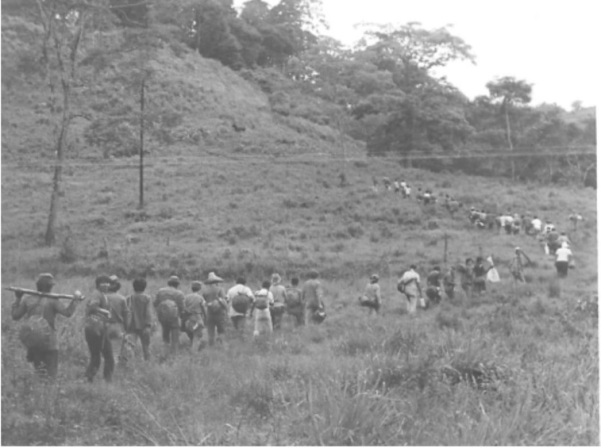

Berta was a pioneer in the movement to defend the ancestral lands of the Lenca from mega projects funded by international capital. Her murder has been interpreted as a sombre warning for other defenders.

Berta was a pioneer in the movement to defend the ancestral lands of the Lenca from mega projects funded by international capital. Her murder has been interpreted as a sombre warning for other defenders. Honduras has also received funds from international climate funds which seek to promote clean energy. Investments include hydro-electric projects, often on the lands of indigenous peoples, or poor peasant communities. But in most cases, the Honduran government has failed to consult the indigenous before launching projects on their lands. Neither does the government offer any relocation packages to those whose lands are grabbed, or those who water supplies are ruined by the dams.

Honduras has also received funds from international climate funds which seek to promote clean energy. Investments include hydro-electric projects, often on the lands of indigenous peoples, or poor peasant communities. But in most cases, the Honduran government has failed to consult the indigenous before launching projects on their lands. Neither does the government offer any relocation packages to those whose lands are grabbed, or those who water supplies are ruined by the dams.